BACKGROUND

Journal clubs are a well-documented instructional method and commonly used in residency and fellowship training programs for continuing medical education.1,2 In medicine, journal clubs serve as a method for healthcare professionals to update their knowledge base, promote critical thinking and research, assess validity and applicability of the literature, improve skills in critical appraisal, increase the use of literature in clinical practice, and to influence changes in care practices.3 While journal clubs have traditionally taken place in face-to-face settings, the emergence of technology and social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have expanded the format of these meetings, allowing new literature to be shared virtually and almost instantaneously. This has been especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the need for social distancing drastically changed the way education could be structured and necessitated innovative educational strategies such as remote learning via virtual platforms.4

Despite being extensively utilized in graduate medical education, the use of journal clubs in undergraduate medical education is not as well-documented or universally incorporated. While journal clubs are utilized in medical schools across the United States, there is variance in its form with some programs formally incorporating it in its curriculum5 while others are student-run and available through extracurricular interest groups.6 For pre-clinical medical students, journal clubs may allow for early exposure to specialties, which is known to be a highly influential factor for career specialty choice.6,7 Otolaryngology is a highly competitive field that medical students are often not exposed to in pre-clinical years unless they have had prior exposure or intentionally seek it out. To our knowledge, there are no studies specifically evaluating how otolaryngology journal clubs affect medical student interest in otolaryngology or their perceived preparation for clinical rotations or residency, highlighting the need for further investigation in this area.

Here we report our experiences and findings from piloting a virtual otolaryngology journal club program with medical students at the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine. Utilizing qualitative and quantitative survey data, the aim of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility, value, and utility of incorporating journal club into medical school curriculum. After reviewing published literature on journal clubs in medical education, a list of overall goals we sought to accomplish with the journal club program was created and included the following: a) raise awareness of otolaryngology as a specialty, b) develop an appreciation for research, c) improve ability to critically analyze primary literature, d) improve small group participation, presentation, and communication skills, e) create a forum to discuss and debate medical topics, and f) provide a learning experience that is valuable for clinical rotations and residency.8,9 Furthermore, we were interested in how medical students perceived the role of journal clubs in medical education, whether they would be open to attending future sessions, and if they believed journal clubs are important to include formally in medical school curriculum. We hypothesized that journal clubs would not only increase students’ awareness of the otolaryngology field but would also foster early development of critical thinking and communication skills that could be applied in future clinical experiences.

METHODS

Recruitment

To adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic social distancing regulations, a virtual otolaryngology journal club program was created with overarching goals of promoting scientific literacy and preparing medical students for their clinical years and residency. Medical students were notified of journal club sessions through social media, email, word of mouth, and fliers. Students who registered for the sessions were notified of the study through email and asked to participate in the IRB-exempt research (The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board, February 2021). Participation in the study was not a requisite to participate in journal club. Those who agreed to participate in the study and who attended at least 4 of the 6 journal club sessions were entered in a gift card drawing. Participants who attended 4, 5, or 6 sessions were entered in a $10, $20, and $40 drawing, respectively. There were no other incentives for participating. Participating in the journal club was not counted as an excused absence from other clinical or school responsibilities, so students who attended did so on their own free time.

Journal Club

Journal club meetings were held bi-monthly from April 2021 to April 2022 (6 total sessions). Sessions were 1 hour in length and held remotely via a secure Zoom link. Journal club sessions were facilitated by an attending physician from the Department of Otolaryngology. Journal club topics were chosen by the participants and included clinical topics related to otolaryngology. An average of 2-4 articles based on those topics were selected by the faculty facilitator for the session (Table 1). Outside of facilitating, the faculty did not have a role in the study and were not aware of whether a student was or was not participating in the study. Each journal club session had a specific objective which was created to help accomplish the overall program goals. These objectives were informed by a previous study that surveyed Australian medical school educators on the intended purpose of journal clubs in medical school and were randomly assigned to each topic.9

Surveys

Those who agreed to participate in the study were asked to complete a baseline survey that included basic demographic information and information on prior exposure to journal clubs and otolaryngology. After each journal club, study participants were contacted via email to complete a post-session survey assessing the efficacy of the session in meeting the specific session objective and overall assessment of the session itself. The post-session survey consisted of a series of quantitative questions to measure the engagement of content and effectiveness of session in complementing medical school curriculum followed by qualitative questions to assess take-aways, suggestions for improvement, and possible interest level changes in otolaryngology. Study participants who attended a minimum of 3 sessions were asked to complete a post-participation survey to assess how beneficial they felt the journal club program to be, how effective the journal sessions were in meeting the overall program goals, potential changes in their otolaryngology interest, and their perception on the role of journal clubs in medical education. All surveys were optional and deidentified to maintain the anonymity of the individual responses. Survey questions were informed by a previous single institution study that surveyed medical students on their experience with a mandatory journal club.6

Statistics

Descriptive statistics including mean, median, and mode were reported to describe the sample and outcomes. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Survey answers were assigned a score. For questions with five answer choices: 5 corresponded with a “strongly agree,” 4 corresponded with “agree,” 3 corresponded with “neutral,” 2 corresponded with “disagree,” and 1 corresponded with “strongly disagree”. For questions that asked respondents to rank answers in order of importance, 3 corresponded with most important, 2 corresponded with moderately important, 1 corresponded with least important, and 0 was assigned if unranked.

RESULTS

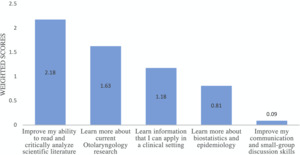

There were a total of 17 medical students who participated in the otolaryngology journal club program and 11 students who participated in the study. The majority of participants were pre-clinical medical students: 64% identified as first-year students and 27% were second-year students, with only 1 medical student in their clerkships. When asked about all prior exposures they’ve had to otolaryngology, the majority of respondents had prior experience with shadowing (91%) (Supplemental Figure 1). Other prior exposures included family and friends (18%), reading (45.5%), and research (27.3%) (Supplemental Figure 1). 82% of participants had no experience with journal clubs and 64% answered that they did not feel prepared for clinical clerkships or residency (data not shown). Specific aspects students did not feel prepared for included the ability to apply basic science in a clinical setting, effectively communicate with patients and other health professionals, and understand how treatment plans were developed or why specific treatment decisions were made. The majority of students agreed that they were interested in otolaryngology for their specialty career and that journal clubs had a valuable role in medical education (Supplemental Table 1). When asked to rank their three most important personal objectives for participating in journal club, “development of critical appraisal skills” was deemed to be the most important purpose, followed by “learning about otolaryngology research,” “learning information that can be applied in a clinical setting,” and “learning biostatistics and epidemiology,” with “improving communication and small group discussion skills” being the least important (Figure 1).

After each journal club session, participants were asked to complete an optional post-session survey that assessed students’ perception of the session and had one question tailored towards whether the session’s specific objective was met. Supplemental Table 2 illustrates the number of participants and survey respondents at each session. There was a mean of 6.5 participants at each journal club session with a range of 3 to 11. The average completion rate for the post-session survey after the session was 69%. Study participants on average participated in 2.27 sessions with a range of 1 to 5. The first journal club session had 8 participants and 6 of them responded to the post-session survey (Table 2). The responses to questions from sessions 2-6 exemplified similar trends to the answers from session 1 and thus are not shown. Table 3 displays participants’ responses to whether the specific sessions’ objectives were met. Overall, respondents were open to attending future sessions, agreed that journal club was a beneficial experience, and agreed that many of the respective session objectives were met.

Medical students who participated in 3 or more of the journal club sessions were asked to complete a final post-participation survey. There were 4 participants who met criteria for completing the final post-participation survey. We received a 100% response rate for the post-participation survey and the respondents agreed that many of the overall program goals were met (Table 4). Answers from the qualitative and open-ended questions demonstrated that students agreed that journal clubs should be incorporated into medical curriculum and that participating in these sessions was a valuable experience (Table 5). Notable suggestions for improvement included having the sessions in person as the virtual format posed difficulties in facilitating discussion and made it more challenging to interact.

DISCUSSION

Journal clubs are a well-documented instructional method that is widely used in medicine. Despite extensive use in graduate medical education, the use of journal clubs in undergraduate medical education is not as well-reported. The limited literature on medical student journal clubs, and moreover lack of otolaryngology-specific journal clubs, can make it difficult to determine how medical students would perceive a curriculum that includes journal club. Our pilot program was very well-received by participants who felt the journal club program to be beneficial to their education and would attend future sessions. The findings from this pilot study support the value of journal clubs for medical students and may encourage implementation of a more formalized journal club curriculum for medical student education.

Given the overall competitiveness of otolaryngology, successful matching is often dependent on a candidate’s research acumen. As such, it is advantageous for prospective applicants to realize their otolaryngology interests early in medical school to allow for adequate mentorship and time for research involvement. Survey respondents agreed that participating in journal club raised their awareness of otolaryngology as a specialty and their appreciation for research. Furthermore, respondents agreed that the journal clubs provided valuable information about otolaryngology that they did not previously have and that they learned information they felt could be utilized in their future clinical rotations and residency. Our findings are similar to Berman et al’s study that discussed how medical students participating in surgery journal clubs reported gaining more insight on surgical subspecialties and felt more prepared to succeed in clinical rotations and residency. In this study, Berman et al. created an in-person journal club at the Eastern Virginia Medical School. Their journal club format entailed medical student(s) presenting a PowerPoint presentation of the journal article. An attending physician was present to provide feedback on the presentation and guide discussion on critiquing and clinical implications. Following these sessions, the participants were surveyed to assess whether the journal club goals were met. They found the participants did find these sessions to improve their literature analysis skills, expose them to different surgical specialties, and help prepare them for clinical rotations and residency.6 Taken together with the results from our pilot study, these findings suggest that having an otolaryngology-specific journal club could provide further support in preparing students for their future clinical years and improve prospective applicants’ research experience.

Medical education was greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with social distancing protocols making it challenging for medical students to engage in face-to-face activities. While survey respondents felt that the journal clubs could be more effective if conducted face-to-face, the virtual format of our journal club allowed for continuation of medical education during the institution of pandemic barriers. Our findings suggest that a virtually formatted journal club can be effective way to foster essential nonclinical skills such as improving ability to read and critically appraise literature. This is consistent with a similar multi-institutional study conducted by radiology departments at Weill Cornell Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, and a community radiology group, Roper Radiologists, that discussed their experience with implementing a virtual journal club to continue radiology education with medical students, residents, and fellows.10 In this study, Belfi et al. held a virtual journal club via video conference platforms for multi-level learners from March 2020 to April 2021. Initially, the format of the journal club entailed a resident and fellow each presenting a journal article (methods, results, limitations, discussion) and holding a question-and-answer session. Refinements were then made to subsequent journal club sessions to be more pedagogical and centered on medical students. The authors found the virtual journal club was well received by all participants. Specifically, the medical students and residents found the information current and engaging, and the fellows felt the journal club strengthened their knowledge base and enhanced their communication and teaching skills.10

In our pilot study, the only program goal that respondents felt neutral on whether it was met was “creating a forum to discuss and debate medical topics.” This is likely attributable to the journal club being held virtually. Although many changes were made in the medical student curriculum to accommodate for the social distancing requirements of the pandemic, it is known that learner engagement can be more challenging over virtual platforms due to technology difficulties and participant multi-tasking such as having alternative reading materials open.11–13 Technical issues and challenges with keeping all participants engaged and vocal were also reported in the study by Belfi et al. Despite these challenges, our data supports that a virtually formatted journal club can still accomplish many objectives that an in-person journal club can.

There were several limitations to our study including small cohort size and missing participant surveys which could lead to underestimation or overestimation of findings. Moreover, the journal club was a collaborative extracurricular event with the Otolaryngology Student Interest Group and as such, participants were likely self-selecting in that those medical students who participated were most likely already interested in the specialty (Table 4) and their responses are potentially not representative of the general medical student body. Although the journal club invitation was extended to all the medical students, because it was offered through the Otolaryngology Student Interest Group, there is the possibility of selection bias of who chose to participate. Future steps would include broadening journal club participation beyond the interest group to increase both cohort numbers and widen the audience. This would increase the number of medical student participants who may be undecided on their specialty choice allowing us to improve our assessment of whether a specialty-specific journal club could increase their interest and explore the specialty further. In addition, the scope of this study did not include how journal club participants performed on their clinical rotations or their successes with matching into residency, limiting the objective analysis of the long-term impact of this curriculum with respect to these goals. Furthermore, given the nature of our survey study, all data collected was inherently subjective and would not be able to objectively assess if participants indeed had improved their ability to critically analyze literature. Further investigations will aim to include pre/post intervention knowledge or skill assessments for students who participated in the journal club sessions, providing objective data for this goal. A 2017 pilot study by Williams et al. utilized basic science quizzes to assess clinical medical student’s knowledge gain and retention after journal club.14 Medical students in their surgery clerkship were randomized either to participate or to not participate in a review session about basic science related to the journal club articles. Students were given a 10-question quiz twice throughout the clerkship, after 1 day and again after 3 months, evaluating students’ retention of the basic science and the clinical implications of the paper. They found that students who were randomized to basic science review scored better on both the basic science and clinical implications sections on the quiz given one day after the journal club, whereas 3 months later they only scored better on basic science questions. Based on these results, the authors concluded that incorporation of a basic science review of journal club articles improved knowledge gain and retention.14 Similarly, we could employ an analogous methodology in a future study with pre/post knowledge tests to assess objectively if journal club participants indeed have improved ability to critically analyze literature or knowledge gain. Additionally, a future longitudinal study evaluating a medical student’s performance on their clinical rotation, evaluating the number of students who pursue an otolaryngology rotation, apply to otolaryngology and/or are successful with matching into an otolaryngology residency may provide further insight on this impact of a formal journal club curriculum. Lastly, now that social distancing restrictions have lessened and our institution allows for in-person meetings, potential refinements for future sessions could include in-person sessions, as well as sessions that are more student-run where senior medical students can facilitate the sessions and faculty are only present for guidance as needed. These changes may potentially address the neutral answer in our results of creating a forum for discussion and debate of medical topics.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this pilot study demonstrated that medical students are eager to participate in journal clubs and feel it is an overall value-added activity outside of their formal medical education. The journal club format may be an effective way to help students develop an appreciation for research and gain valuable early exposure to specialties outside of clinic. Many future steps can be taken to improve on this pilot curriculum and aid in future specialty-specific journal clubs and medical curriculum planning.